15 years ago, we at Cyclefit started plying our trade in a relative thought-vacuum about cycling biomechanics. This void gave us all licence to befriend the dangerous twins ‘feel’ and ‘folklore’ when it came to settling our bike-to-body arrangements. Appeals to their close cousin ‘common-sense’ also has risks because so much of cycling biomechanics is counter-intuitive and therefore inherently hidden from our conscious mind.

For example, when we are interviewing a new and injured client, it is very common for all the focus to be on what is perceived to be the ‘problem’ leg and for the other leg often to be described as ‘fine’ or even ‘better engaged’. Only later, when we scan the pedal stroke, do we find that the ‘problem’ leg is doing much of the work compared to its under-achieving partner. The ‘good’ leg feels better because it is relatively under-used and therefore more rested. As I say, this may be considered counter-intuitive because this is not how it ‘feels’ to the rider.

Almost all of us have, at some point in our cycling careers, been coached or advised to pull-up on the pedals by well-meaning friends and peers. And we have all dutifully tried our best to visualize ‘spinning plates’ or similar; because the logic of pulling up is irrefutable. There’s a longer and smoother pedal stroke at the end of the rainbow. Or is there?

Our bodies are perfectly evolved to deal with the ancestral environment of 150,000 years ago, when running and throwing spears was more important than getting gold at l’Etape or winning a race at Hog Hill. As a consequence our pedalling function will always be an extrapolation of our inherited walking or running function.

The case against the Upstroke

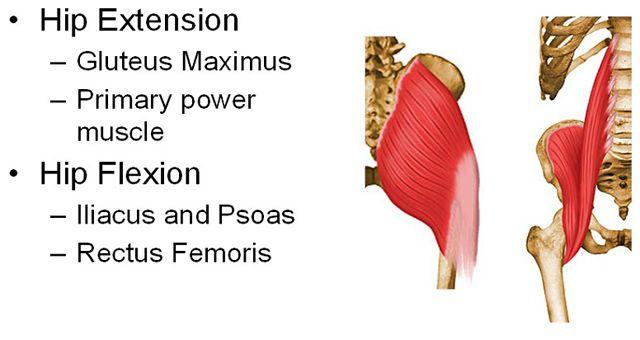

- Back to our evolved selves – look the image on the left and in particular at the huge mass of the glute muscle – our primary hip-extensors (opening the hip). The glutes make up the biggest and most powerful muscle-group in our body. This is a prime ‘moving’ muscle group, employed in exerting the forces that propel the walker or runner.

- In contrast, the image on the right shows the smaller hip-flexors, which pull the thigh upwards. Relatively small compared to the glutes, they are clearly not evolved to produce a huge amount of power. In walking and running the hip-flexors simply move the legs, each lifting the knee towards the chin against the force of gravity acting on that particular leg.

- Unlike when walking or running, where each leg must move independently, in cycling the two legs are linked together by the cranks and bottom bracket axle. Why, then, bother pulling up on the right when you are already pushing down with your biggest movers – i.e the glutes and quads?

- Brain space. It is thought by some earnest biomechanists and cycling physios that we simply don’t have the available neural RAM or proprioception to be able to generate any meaningful force on the upstroke at anything approaching full cadence and full power. Try it for yourself and that is certainly how it feels.

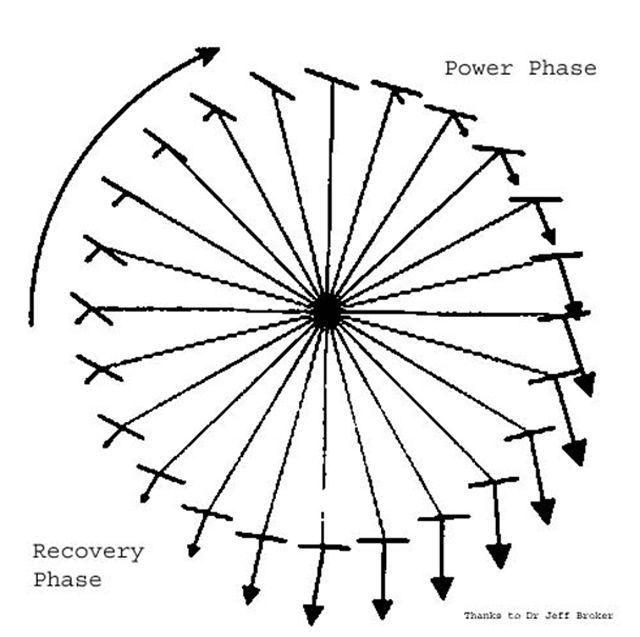

- The research says we don’t – Dr Jeff Broker has done extensive pedalling kinesiology tests on 100 elite and professional cyclists over 10 years and his data shows that not one of them produces a meaningful upstroke. So what hope is there for the rest of us?

Look at the diagram at the top and you will see that even elites and pros have a negative loading on the pedal during the ‘upstream’ or recovery phase of the pedalling circle. That is to say that even they don’t produce enough force at the pedal to offset the effect of gravity on their uphill-moving leg!

Problems associated with pulling up on the pedals

- Lower back pain and numbness which can result in a loss of power.

- Tightness and pain in the hip.

- A feeling of floating and disengagement.

- The feeling of a gap between the foot and the inside of the shoe

- In extreme cases - impingement of the Iliac artery

Pulling up isn't always a conscious act

We see many riders that have a combination of the symptoms listed above who are pulling up on the pedal on one side only; this is very often caused by their foot mechanics which leads to poor foot/shoe contact on the downstroke. To compensate the same leg will pull up more to even out the power distribution between both legs, on other occasions the opposite leg might over compensate to help the other.

Using the Spinscan software on our Fit Bike we can see where the power distribution is in the pedal stroke; by adjusting the bike position, improving foot control with footbeds and pedal coaching we can even out the power distribution and alleviate many issues.

Sam Bennett of Bora-Hansgrohe demonstrates excellent posture and pedal stroke

So how should you pedal?

- Don't over think it.

- Keep you cadence between 85 to 105 rpm; bigger riders with more muscle mass tend to have a slower cadence, don't try and fight gravity.

- Your body is trying to run, so open up your hips and ride with a long back, spring off your toes at about 5 o'clock to help stabilise the ankle and the rest of the kinetic chain.

- Don't pull up!